Since the first high quality seismograms and the development of theoretical models in the 1960s, it is established that earthquakes ruptures are complex (e.g. Archuleta and Frazier, 1978; Das and Kostrov, 1990). Over the few seconds or minutes of its duration, earthquake ruptures can go through various stages of acceleration, arrest, large slip or no slip. Given our inability to directly measure what is happening on the fault, remote imagery of fault slip evolution on the fault is a key element to understand what controls earthquake ruptures. It is also a necessary step towards a finer description of the seismic cycle (how ruptures repeat over time), and the prediction of generated ground motions (what causes building destruction and tsunami waves).

Hundreds of studies have investigated this complexity using data, first mostly relying on data from the global seismic networks and then, around the 1990s, using satellite based technologies such as GNSS, InSAR or optical imagery.

Despite the continuous development of instrumentation, earthquake ruptures (and by extension any slip episode on a fault) remain challenging to image: signals are always recorded at the surface, spatial and/or temporal resolution of data is usually limited, data might be biased (e.g. collected one month after the earthquake), our knowledge of the Earth structure is often limited, as well as the physics of the processes involved. To address these issues, my collaborators and I, have developped different methodological approaches to address a number of limitations:

incorporate more data, of different types and sensitivies. In the case of well instrumented earthquakes, our description of earthquake rupture can be based on teleseismic data, near-field strong motion, tsunami, GPS, radar images and/or optical images (e.g. Bletery et al.,2014),

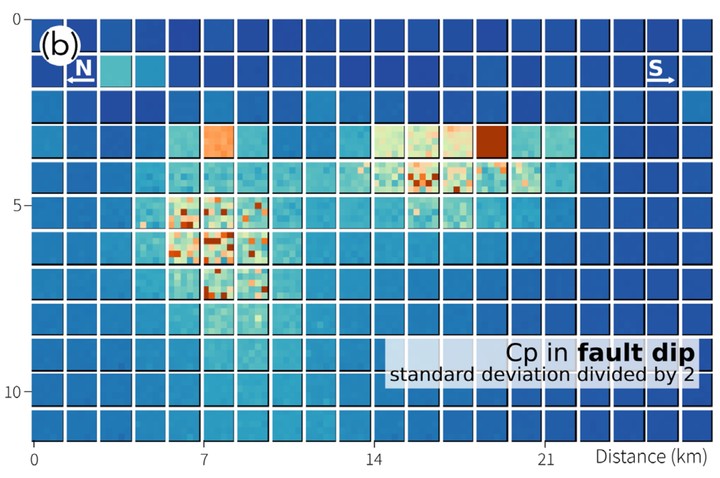

analyze data with probabilistic (Bayesian) algorithms. This formalism limits the amount of ad hoc assumptions (e.g. regularisation, imposing a priori information which is not well defined), and allows to estimate uncertainties on our final models (e.g. Simons et al., 2011; Bletery et al., 2016),

devise a formalism to acknowledge model (epistemic) uncertainties. We show that this type of development leads to more robust images of fault slip history. It is a necessary approach given that our knowledge of the Earth structure will always be, at least to some extent, limited (e.g. Ragon et al., 2018),

explicitely account for limitations of the measurements. Very often, data are acquired at the wrong time, with limited spatial coverage, or else. By developping strategies to acknowledge these limitations, it is possible to improve the robutness, and sometimes resolution, of the sought-after model (e.g. Bletery et al., 2018; Ragon et al., 2019),

move towards more advanced physics (forward problem), when possible and useful. Within the PhD project of Hector Alemany, and in collaboration with Vadim Monteiller, earthquake wave simulation in 3D complex media.